Part one of this series covered the very basic physiology of the autonomic nervous system. Part two discussed some of the many practical assessment strategies of the ANS. Here in part three we’ll uncover some practical applications for your programming.

As was explained, after taking an orthostatic heart rate I suggest holding it up to Vladimir Issurin’s recommendations. Here they are again:

- 0-6bpm fluctuation in waking hour heart rate is normal.

- 6-11bpm change means you are not recovered completely

- 11-16bpm changes means you are really not recovered and need rest

- 16+bpm means you are overtrained

Acute Perspective

We’ll start at the top and work our way down. The first reading (0-6bpm) is normal and the obvious application is to continue training as planned. The second reading (6-11bpm) should not overhaul your training plans for that day but can simply indicate that if you continue the same life pattern, be it through training or other life stressors, you’re headed towards forced rest/recovery. If you previously were exposed to some type of stress outside of your training regime that could be the reason for this particular reading and simply removing that life stressor will bring the reading back down and training should continue as is throughout.

The next reading (11-16bpm) is where we have a bit more options to choose from. With this heart rate you need to either omit training that day, reduce training stress considerably, or engaged in a recovery activity. What is a recovery activity? Many things. But if you’re like me and desire movement instead of simply “taking the day off” or using other modalities (that can still be great choices) here are some simple, of the many, guidelines for structuring recovery sessions:

- Perform 20-60min of work keeping HR in the 120-150bpm range.

- The work you perform at the muscular level here should be low to moderate intensity (nothing heavy) and staying in the appropriate HR range.

- Work activities include tempo runs/exercises, circuits, mobility circuits, the bike, the versaclimber, etc. are all fair game. Just stay in the 120-150 range and don't use heavy items like a 1-6RM. As you'll see this is not high intensity work at all.

- Rest periods between sets/activities are totally up to you. You could work up to 150 and stay there for the entire 20-60min or you could work up to 150, rest back down to 120, and then go again. Do not overcomplicate this.

The next reading (16+bpm) absolutely indicates forced rest (from an acute perspective). Do not train. Go home and rest while considering if any life stressors outside of training could have caused this. You should also look at your programming to see if the culprit is simply not adequately programmed recovery periods. However, if this was planned overtraining, you may proceed. This leads us to a more chronic perspective. . .

Chronic Perspective

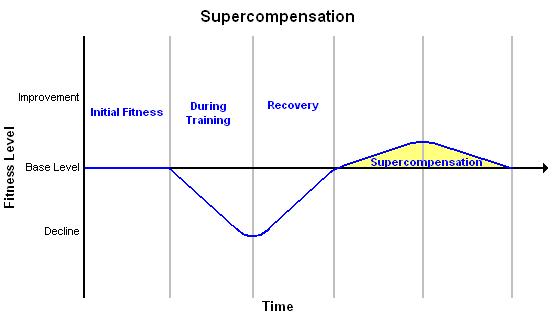

As I mentioned before (and posted some excellent YouTube videos about), stress plays a major role in the training process of athletes whether its novice lifters or well seasoned veterans. As coaches or clinicians we need to monitor this some way in order to better prescribe and manage the training stressor. With that in mind you need to understand how in many cases planned overtraining is part of the macrocycle and very much a cornerstone of results later to come. Indeed, sometimes you purposely want to overtrain your athletes. This will have an even larger effect on their super compensation when the stressor is removed and their bodies rebound in performance way above baseline measures. Yet a discussion on exactly how to do this with periodization is beyond the scope of this blog series. Just appreciate that the method exists and if you did not plan for purposeful overtraining but yet your orthostatic heart says you’re overtrained, you need to back off and reevaluate the situation.

Taking It Back to Respiration

Most of the above deals with systemic physiology however the other aspect to this discussion, as mentioned in parts one and two, was the conscious link into the ANS via respiration. I referenced an assessment video from Patrick Ward on breathing mechanics which are a bit more biomechanical in nature. No need to reinvent the wheel so here are the follow up videos he posted for practical corrections:

Wrapping It Up

So in conclusion, the autonomic nervous is critical. Duh. However we need not dismiss it as too complex to manipulate as there are a number of practical initiatives we as coaches and clinicians can implement with our athletes for better results in the long term. Understanding the physiology is important and appreciating that respiration is our only conscious link into the ANS is equally as high yield.

Additionally, my friend Dr.Craig Liebenson has released three DVD's that are quite promising and you'll be certain to come away with a better understanding and better application for what you do. Check them out HERE!

Just so you guys know I've updated this post as well as the rest of the series. Be well!