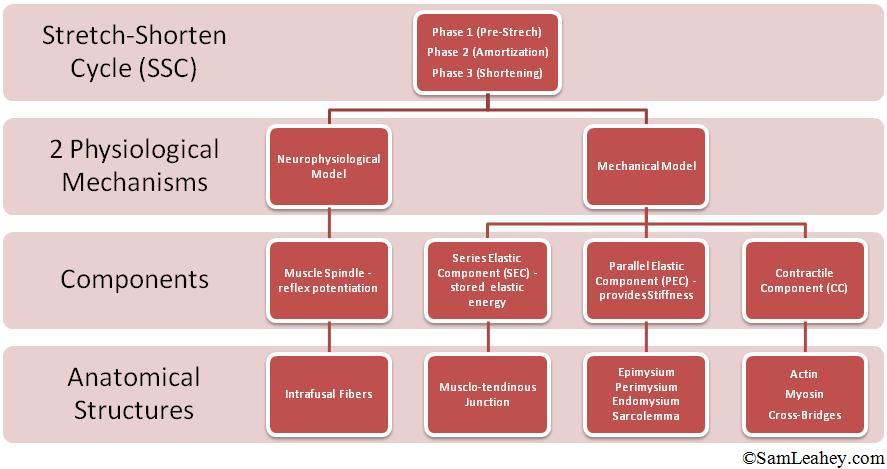

This piece I did for my friend Carson Boddicker's website, who is a great resource in the world of track and field performance and lower extremity dysfunction. I’ll attempt to do this is blog post style (read: short and to the point with as many high yield points as possible). Many refer to elasticity as “reactivity,” “plyometrics,” or the “stretch-shorten cycle” but at the end of the day I believe the term “elasticity” is the most literal and best descriptor of the quality we’re after. Just my opinion. Athletes in most sports will benefit from increased amounts of elasticity in various body segments. Be it the lower or upper extremity or the core, an elastic response by our bodies can yield a much greater output of force, impulse, power, and/or stability. That said we can only attempt to develop our elastic response within the confines of our current levels of mobility, or length-tension relationships. This can be good or bad depending on reference. The elastic response has, for the most part, three phases. The first is defined by a rapid excursion of a joint which actives the “stretch” part of the “stretch-shorten cycle.” Then various bodily mechanisms respond to counteract the rapid lengthening causing a switch from eccentric to concentric contractions. This portion between the lengthening and shortening is term the amortization phase. Said mechanisms of elasticity are illustrated in my diagram below which depicts how elastic energy is stored and released during the stretch-shortening cycle phenomenon:

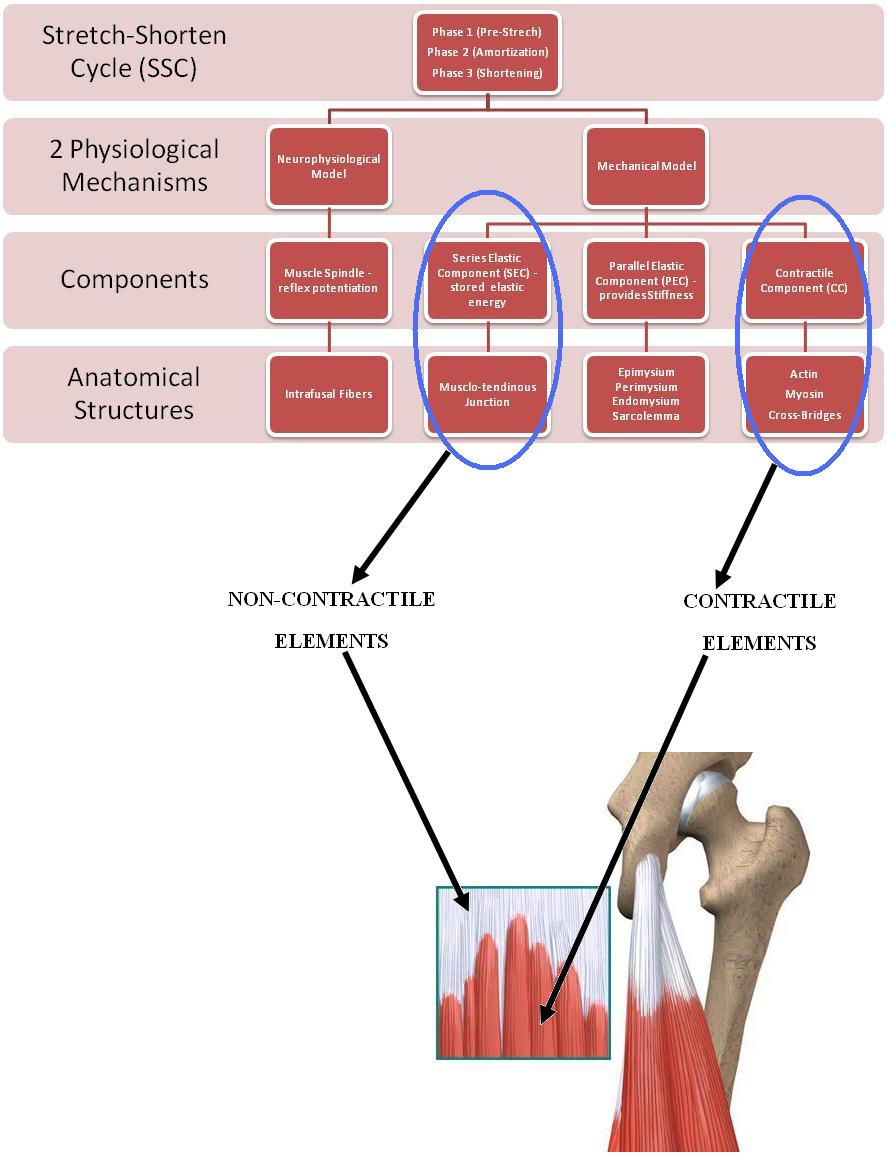

For the sake of brevity I won’t elaborate fully on each constituent but suffice it to say the entire diagram above can be filtered down into a simple dichotomy – contractile and non-contractile elements:

The neurophysiological mechanism of the muscle spindle does not need to be discussed here because we don’t have as much control over it. In time the nervous system adapts and adjusts for the muscle spindle and golgi-tendon organ (GTO) interplay by reducing the effects of the GTO. What is worth elaborating on is the interplay between contractile and non-contractile elements during the stretch-shorten cycle. Said elements both have the potential to store elastic energy and release it causing greater force output. However the non-contractile component (tendon) has much more potential for elastic energy output compared to the contractile component (extrafusal muscle fibers). In the ideal world the percent contribution of force would come mostly from the non-contractile part of the equation. We’re looking to shift the source of our elastic energy production to the structures that can give us the most return.  In order for this to happen, stiffness of the muscle fibers must occur so the “stretch” part of the “stretch-shortening cycle” is shifted to the tendon. Ideally we would have an isometric contraction of the extrafusal muscle fibers so nearly all the elastic rebound comes from the tendon. In lay terms – the red part of the picture of above stays still while the white part stretches out and snaps back into place. It’s healthy to understand the mechanism of our training initiatives. In latter posts, I’ll return with the application of this science for non-beginner athletes. Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and get exclusive content as well as updates on site happenings.

In order for this to happen, stiffness of the muscle fibers must occur so the “stretch” part of the “stretch-shortening cycle” is shifted to the tendon. Ideally we would have an isometric contraction of the extrafusal muscle fibers so nearly all the elastic rebound comes from the tendon. In lay terms – the red part of the picture of above stays still while the white part stretches out and snaps back into place. It’s healthy to understand the mechanism of our training initiatives. In latter posts, I’ll return with the application of this science for non-beginner athletes. Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and get exclusive content as well as updates on site happenings.

Leave a comment