Preface

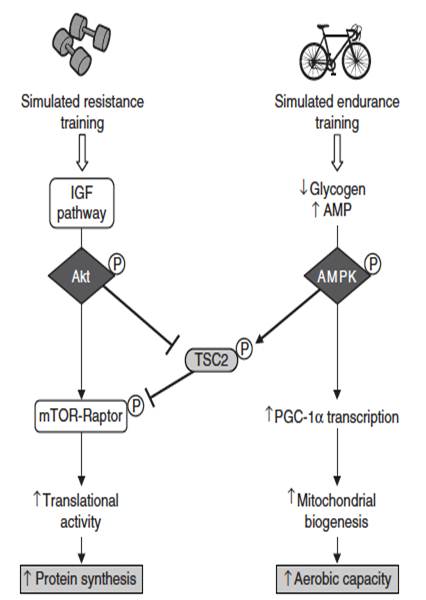

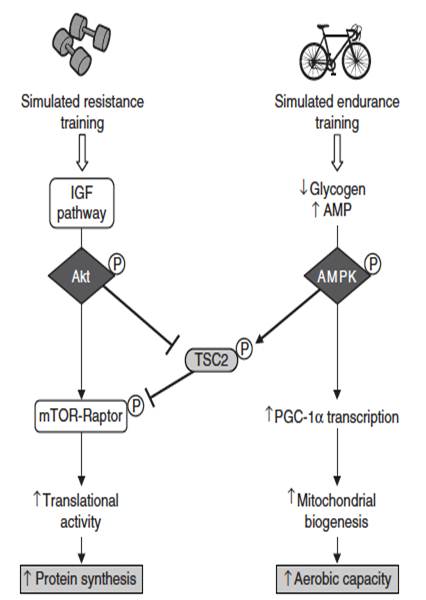

I was recently listening to the StrengthCoachPodcast (episode 103) where my good friends Anthony Renna and Coach Boyle were discussing the information Joel Jamieson and Cal Dietz presented on this year at the Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group Seminar. As was noted, there seems to be some confusion regarding what exactly Joel and Cal were getting at with their emphasis on seeking to develop only one or a small number of qualities at a time instead of trying to train everything at once. During this lecture, Joel showed the below picture (signaling pathways, slide #16 of his PowerPoint entitled Specific Stress Response) and explained how, for example, if you train for Quality X at the same time you train for Quality Y the biological response from each of those exercise bouts could inhibit each other’s adaptation process. In sport science text “human body” and “organism” are used synonymously. In this case the “organism” is being pulled in multiple directions because you are training potentially opposing qualities, and if not opposing qualities, then qualities that may be similar but nevertheless have different directions and therefore pulling the organism in slightly different directions. As a result, the adaptation you get (increase strength, increased endurance, etc.) underachieves and you only get a fraction of the result you could have gotten if you just focused on training a single or small number of qualities.

Why None of This Matters if We’re Not Keeping the Big Picture in Mind

So, generally speaking, in “classical” periodization what does “training all qualities at once” refer to? Concurrent programing. What does “only train a single or a couple qualities at once” refer to? Block programing. In fact, soon after Joel presented the above slide in his talk he then showed a slide entitled “The Bottom Line” where he states – “Higher level athletes will benefit the most from ‘block training’ where either mechanical or metabolic loading is the primary emphasis in the training block.” The first three words in that quote are the key to this whole blog! It is not that Joel Jamieson is claiming every single athlete of all training levels ought to use programming which focuses on a single quality or two thus providing a concentrated or specific training stress. It’s just that this type of training is most beneficial for advanced athletes. So it is a question of when to use it, not either-or. Signalling pathways that inhibit each other are not inherently a bad thing. Tis only an issue when this stops yielding acceptable results and a new threshold can only be reached by a more concentrated/specific stimulus. But why would this benefit advanced athletes most? How does one define “advanced”?

The Real World Application & Why

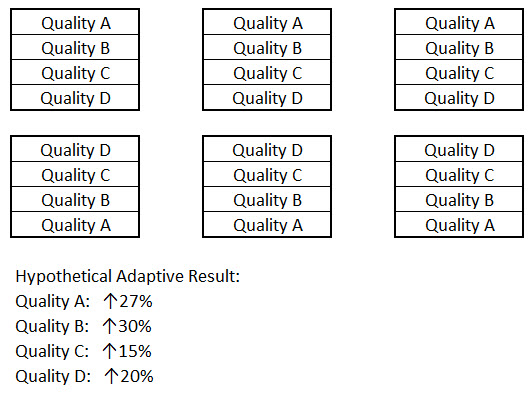

With above in mind, we can now answer why it makes sense and is suggested to progress from “concurrent” style to “block” style programming. Consider the following hypothetical situation devoid of context – a snapshot of six random training sessions within a concurrent program:

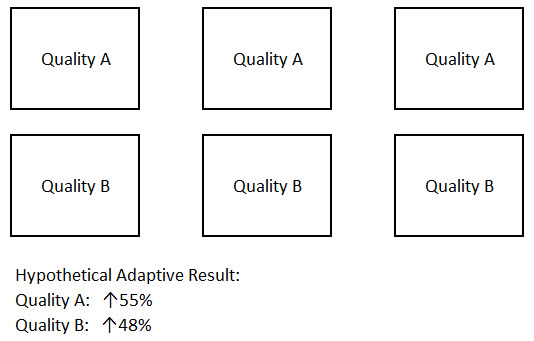

Realize the order of qualities trained in this scenario is irrelevant; this is just for demonstration. So, in this concurrent program you train everything in every session. At the end of the program you test and find the above hypothetical improvements. Notice the percentages do not sum 100%. The human body doesn’t work like that. Anyway, you’re satisfied with the results and so you continue programming in this manner for next phase of training. You test and get similar improvements again. Excellent! Depending on the athlete, this could keep happening for years! And that is just the point here. It’s all about the rate of adaptation! When an athlete no longer improves biomarkers when training everything all at once, by the standards YOU set, you know it’s time to move on to something more emphasized, more concentrated, more specific. For example say after a stagnation period you determine that Qualities A and B are most important for success in the hypothetical sport. You therefore design a program emphasizing those qualities and below are a random snapshot of six training session in the program:

You test your athlete at the end of this new block style program and find a big improvement in Qualities A and B whereas in the previous concurrent style program you were stuck at a certain value or you were only getting very small results. And in this discussion, by “results” we’re referring to quantifiable biomarkers/qualities.

All this just to say – the more advanced the athlete the more specific/concentrated the training stimulus needs to be for continual improvement. If you’re still getting results with concurrent programing then stick with it! Why use something more aggressive? ALWAYS use the smallest/less aggressive stimulus necessary to get the desired adaptation/result. With the long term athletic development in mind this makes perfect sense. You can start the beginner athlete by training every quality at once and when they stop responding then BEGIN to emphasize certain qualities, when they stop responding to that, switch to an even more focused approach. Furthermore, if you’re “advanced” athlete is still getting what you define as acceptable results from concurrent programming – are they really “advanced”?

This is also to say that, yes, in the concurrent program you are simultaneously and purposefully training qualities that inhibit each other’s adaptation. That is ok! As long as the biomarkers are continually improving it doesn’t matter that you’re not reaching the full potential of every single quality at once. The tradeoff is that you’re getting a smaller rise in ALL qualities at once as opposed to a bigger rise in just one or a few qualities at once. “Concurrent” versus “Block”.

In the concurrent program – It's OK that the molecular biology conflicts as long as you’re satisfied with the improvements being made.

This is one thought process behind much of Yuri Verkhoshanky’s paradigm and one that I align myself with as well. Small and less aggressive stimulus to bigger and more aggressive stimulus. Let the quantifiable results determine the rate at which you progress the program style.

Guiding Questions & Answers

So with this thought process in mind I know readers are thinking:

– How do you know exactly when to switch from concurrent to block?

– In other words, how do you stratify “beginner” from “intermediate” or “advanced”?

– How do you know what qualities to key in on when they’ve plateaued on concurrent programs?

– What does an actual concurrent or block type of program look like in real life?

– And a ton more . . .

The answer – it depends! On what? YOU! Only you can decide what rate of adaption you label as no longer acceptable. Only you can decide whether the increase in biomarkers is good enough for your situation or not and you need better result from training. Yes, I am suggesting that the difference between a “beginner”, “intermediate”, and “advanced” is partly due to rate of adaptation in your training system. The other part is sport mastery, aka skill level, which is the next piece in this discussion. But first, what happens when you attain a new client who is “advanced” by sport skill standards (professional athlete say) but has never really trained before in their career? You use your brain! This is part of the coaching profession – being forced to make non-ideal decisions. Should you use a concurrent program because they might experience an improvement in many qualities at once or do you use more of a block type program because in the long term model that is where “advanced” athletes end at? Who knows! Logistics will also play a huge role in this. It’s up to you as an evidence-based coach (be sure you know how I define “evidence” – experience is a part of it).

If you’re programs are resulting in continual enhancement of qualities/biomarkers but they do not correlate with enhanced performance markers then something is wrong. You might have chosen the wrong qualities to focus on when training for a certain sport or event. Meaning, you have to analyze the sport/activity to know what to train for. What type of analysis should you use? Two fold – biomechanics and physiology. Understand the biomechanical and physiological underpinnings of your sport/activity and you will easily identify the qualities that affect it the most. This is another thought process of Yuri Verkhoshansky.

As for concurrent and block style programming examples – there are legions of them and all of which are largely differentiated by semantics. If you keep the main point in mind – emphasizing versus not emphasizing qualities – then you should be able to sift through the various authors work and coaches proposed programs to decide which you can model after for concurrent and which you can model after for block.

Lastly, as a note to contrarians on the internet, concurrent and block are just some of the programming models. I am well aware of the huge continuum of other options – undulating, linear, vertical integration, American conjugate, etc. etc. etc. and a zillion other names many of which are governed by semantics. Just appreciate this non-emphasized to emphasized thought process that I’ve presented here in this article.

These are a handful of information. Thanks for sharing this well-written article to us Sam.

Looking forward to read more of your blogs.

Rick Kaselj

<a href="http://ExercisesForInjuries.com">Exercises For Injuries</a>